I was planning to write about this video game I’ve been grinding this winter — Slay the Spire — but inspiration struck, and that’s what the newsletter is for: real-time reporting on the asylum proceedings. I’ll probably be playing StS next week just as much, so it can wait. As to my distraction, I returned earlier in the week to a background project I’d been putting off for a long time, namely watching Pretty Cure, a mid-’00s magical girl anime. (What, children’s culture is basically my career; I watch a lot of cartoons.) It’s old-style hella-long meandering serial tv, so not a trivial task. Something like 50 episodes in the first season alone.

Anyway, digesting the magical girls and their cosmically determined conflict with the dastardly “Dark World”, I realized that Pretty Cure is apparently set in the same world as Hellraiser, the late ’80s British horror movie. Friends know that I have developed a slight obsession about Hellraiser far removed from its objective merits, so I’ve been seeing Hellraiser here and there, sneaking Platonic peeks at me beneath the surface of all kinds of things. After the most recent bout of let’s say cosmological inspiration passed, I realized that this is actually my newsletter feature for the week — it’ll do me good to paraphrase some of my neo-platonistic Hellraiser ideas. Just a little bit, though; won’t be a newsletter anymore if it’s more than a succinct summary.

Intro to Hellraiser

Hellraiser is a horror fantasy franchise based on a Clive Barker novel and popularized by a trashy cash-grab movie series that found some modest success in the ’90s. I’ll just… note that the movies are at best mediocre as movies go, and that I wouldn’t care about Hellraiser one way or another if it wasn’t for the excellent yet uneven Epic comic book run from the early ’90s. Hellraiser is the kind of dingy thing that attracts me: lots of potential with some major execution issues. If you want recommendations, maybe watch the first movie, probably read Hellbound Heart (the original novel), but definitely check out the comic book run.

The Hellraiser mythology concerns itself with Earth-Hell relations in a peculiar postmodern cosmology that seems Judeo-Christian in only the most superficial way. (Apparently enough so for the American movie studio that’s been running the franchise to the ground for the last 30 years, but what do I know.) The “hell” accessed by the mysterious portal device, the Lament Configuration (a puzzle box of 18th century French manufacture), is inhabitated by transhuman mystics of the Order of the Gash, an orgiast cult in service to a sorta-Lovecraftian lord of Order, Leviathan. This is all total horror fantasy stuff: monsters and gore are not the point, the mythology and its underlying thematic meanings are the interesting part. Why would anybody wish to attract the attentions of the demonic Cenobites? In what what are they “Demons to some, angels to others”? What happens to human passion when hedonistic urges are ritualized into dark magic?

The franchise is also very much defined by the fact that its central conceit, the “Order of the Gash”, is supposed to be a fantastic horror take on sexual deviancy and how the hedonism inherent in postmodern lifestyle interplays with the notion of Hell, yet the culture industry that enmeshes the franchise basically makes it impossible for Hellraiser products to go beyond sordid titillation in treating with the subject matter. Most of the thematic content is left in subtext, if left in at all, for BDSM is too scary outside pornography. Thence the monster slasher nature of the movies.

The attractive thing in Hellraiser is its human-centric yet alien (transhuman horror, to be specific) cosmology that lays bold mythological foundations without resting upon prior work, yet managing to feel authentic all the same. It’s not quite Lovecraftian (too postmodern and transhumanistic for that), and it’s definitely not Biblical, but I can nevertheless suspend my disbelief about the existence and magical theory of the Order of the Gash. The more I figure out what Hellraiser is telling me about the nature of its cosmology, the more interesting it becomes.

So let’s get some world-building into it

So, Hellraiser obviously doesn’t have much in the way of core canon, what with the various rights having ended up in the hands of random culture industry robber barons, generally less committed to the literary arts than Clive Barker at his best. You have to pick and choose which bits are the true Hellraiser for yourself, which is of course something I am entirely comfortable doing. Headcanon ahoy!

I wrote a succinct take on the Hellraiser cosmology a couple of years ago on a lark: I was creating rpg scenarios for Tales of Entropy, a scenario-based blood opera story game, and wanted to make one about Hellraiser just to see how a movie adaptation would look like in the game. Part of the Entropy scenario conceit is a compact introductory text that is read aloud to the the play group at the beginning of play. I struggled with what to say about Hellraiser here, but then wondrously crafted something that personally felt very cogent, very powerful as a summary of what it’s all about. I’ll just quote the relevant part here:

Let me tell you, for this is the true nature of the cosmic weave: numberless emanations of the One, shadows of shadows upon shadows, layered like autumn leaves in thick, undisturbed quilts. Elderly planes of existence, slowly putrefying, achieving the anaerobic stasis of utter stillness.

We are the quick. Our reality is young, young and shallow. Boundaries are thick and hard. Quick, vital, yes, but also shallow, ignorant. Lower realities are old and compressed, still. We term it Hell.

Labyrinth, and in its midst unknown God, Leviathan. In His timeless abstraction, unchanging punishment He rests, the make and measure of Order alone.

Today the privilege of serving His will, the Will of Leviathan, belongs solely to the cenobites of the Order of the Gash; they are humans and devils, explorers of the integral flesh, masters of pain and pleasure. Occult literature terms them Hierophants of the Flesh, for theirs is to bring the supplicant to the understanding of Leviathan.

On Earth only little is known of the unspeakable doctrine of the Order of the Gash, for the cloister of the Order sits in the depths of the Labyrinth, in the place where the shadows meet; only rarely do the Cenobites walk the Earth, only when the call comes for one to join the many. Once mortal, now they are the devils whom others in their folly would summon. Once human, yet the Order of the Gash tries the human flesh, it sets the form of both body and mind. The Cenobite discovers the outer limit of the experience he so thirsts, and breaks through beyond the pleasure and the pain.

(The scenario is in the Entropy scenario database. Intone aloud in your best storyteller voice for proper effect.)

The above is close enough to standard sources that you’ll need to be something of a Hellraiser scholar to be able to tell me that it isn’t, <smirk>. The core conceit of my “neoplatonic” Hellraiser cosmology is to explain and define the “phenomenon of hell” without falling into the Judeo-Christian trap that seems to haunt many a dull-witted simpleton working with the franchise. The Cenobites are not demons, they do not tempt sinners, and there certainly isn’t an implicit God involved in anything that happens between a man and his demonic puzzle box in the privacy of his own bedroom. The cosmos implied by the best bits of Hellraiser is something much more original than that.

Magical girls and higher realms of power

Let’s go back to Pretty Cure for a moment, though. My mythopoetic brain parts connected a magical girl anime with a grubby ’80s horror franchise for a specific reason: the bad guys of the show, the Dark World and its Dark King, have some features that, if you squint, make them sorta seem like devils of the neoplatonic cosmology I define above. Specifically, the Dark World is an energy-starved, incomplete dimension that feeds on higher worlds to sustain itself; while its denizens are more world-weary and less naive than the teenager protagonists, they also wield the energies they steal from the world in a much more sophisticated way, making much of what little they master of the nature’s bounty. They even have a passive yet masterful dark godform orchestrating their every thought and deed in a supreme display of fascist hierarchy.

Sure, you could read all this in a Buddhist context, too, but where’s the fun in that. Let’s rather posit that you can write a very stereotypical magical girl “underworld” that is near kin if not the exact same world that the Order of the Gash and their abstract godform Leviathan live in. You don’t need to sweat to make the thematic resonance work.

This stray idea then inspired me to explore the other side of the cosmology, the higher dimensions implied by the neoplatonic cosmological model. (This is something that core Hellraiser material doesn’t really address, unless you consider the attempts to shoehorn a Christian mythology into the series to be core.) In Pretty Cure this would be the “Garden of Light”, a heavenly otherworld from whence the magical girl magic and the cute animal sidekicks come from. It all seems to fall in line rather neatly when I compare what we know about the neoplatonic higher worlds with Pretty Cure:

- The neoplatonic upper worlds of my imagination are younger emanations, closer to the ultimate godhead, with more space and energy and less matter and intricacy. Magical girls get their magic — in Pretty Cure and more generally as well — from a seemingly infinite font of pure holy energy, only limited by their personal capability for drawing and shaping the power. The connection with a higher, more energetic realm empowers them.

- Younger and more energetic emanations are subjectively speaking simpler, more archetypal worlds, for the greater energy density (I use many modern physics analogues in discussing this cosmology; read it as an analogy, not literally) makes it impossible to sustain fine material filigree. This seems to match magical girl experiences: their magical otherworlds are, indeed, more spiritual, less material, simpler and purer than the baseline reality of the protagonist.

All in all, I think that I’ve found some pretty solid precepts for figuring out what the deal is with the higher worlds in this developing neoplatonic fantasy cosmology. It’s not Heaven in a Christian sense, but those worlds do exist, and they can influence the mundane reality, and even work as a counterpoint to the demonic underworlds as in Pretty Cure. More importantly, I have some inklings of what the horror fantasy potential in the higher dimensions is like, once you get away from the assumption that the higher worlds are particularly friendly to mortal flesh. (Hint: it’s not self-satisfied “angels” sermonizing Pinhead the Demon about God’s plan like in the latest Hellraiser movie.)

What is this for?

Just to be clear, I have no idea if I should use this world-building stuff as a kernel for a more philosophically inclined take on Hellraiser, or for a funky western yet non-Christian mahou shoujo thing. (Maybe something like Miraculous Ladybug, except with the Korean elements substituted with toga-wearing stoic philosophers.) Ordinarily I’d say “why not both”, but due consideration tells me that a Pretty Cure x Hellraiser fanfic would be… well, it’d be for mature readers only, and wacky as fuck.

If nothing else, this sort of consideration will make running e.g. Sorcerer easier — Hellraiser is the original Sorcerer setting, insofar as there is such, and if I got a crew interested in tackling the game, I could well see myself drawing on this neo-platonic cosmology stuff for it. “Demons” would be quasi-real phantom denizens of lower worlds far older than the mundane, while “angels” are searing energy constructs from worlds so bright that they can barely observe the mundane reality at all.

Anyway, that’s enough about the neoplatonic cosmology thing for now. It’s a newsletter, not an essay platform. I’ll add this thing into the polls next month, and maybe I’ll write more about it later. It would probably help the audience appreciate what I’m babbling about if I explained more about the big picture in fantasy cosmology building, too; the interesting bit about the thing I’m calling “neoplatonic fantasy cosmology” is, after all, that it’s very European without being Abrahamic, Gnostic, pagan or materialistic; it is its own thing, and therefore fresh and neat.

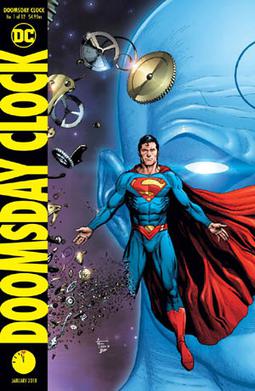

Reading Comics: Doomsday Clock

Scheduling being the devil’s drudgery that it is, I’ve had a week free of all kinds of gaming assignations. I’ve been reading some superhero comics instead, and therefore you’ll get a bit of capsule review on some stuff. For background context, I consider myself relatively well-read on American superhero comics of the 20th century, but as with many things, I’m merely patchily familiar with what’s occurred over the last 20 years. I read things now and then, when the mood strikes me.

The proximate inspiration for the comics-reading came from my remembering that Doomsday Clock had probably been finished since I read the first-most issues last fall. It’s a DC Comics mini-series, a sort of sequel to Alan Moore’s seminal Watchmen and a cross-over with the main DC universe. The work is firmly in the “event” format of superhero comics publication, with all of the implications that has in comparison to routine runs of comic serials.

As is the nature of modern superhero comics, particularly at DC, Doomsday Clock is relentlessly pompous and self-referential: I cannot imagine why I would ever recommend Doomsday Clock to a non-hobbyist. The big attractions are some basic character drama between familiar characters (e.g. “what if Lex Luthor and Ozymandias met up”) and the writer Geoff Johns’s cute cosmological theory about how and why the DC superhero multiverse gets rebooted at what seems to be every five years nowadays. Amusing for the hobbyist who’s already hooked into this stuff, but meaningless for a general audience.

Personally I found it interesting enough to read to its conclusion, but then I have a low threshold for finishing something I’ve already started, and I like world-building, so the cosmological “mystery” was entertaining. Thinking back to it, the event-nature of the book was what grated me the most: it’s pretty clear that the book does not actually have a plot per se, and it only has a topic insofar as it demonstrates the writer’s fridge logic about how the DC universe functions. Superhero comics have been like this a lot over the last few decades: minimal storytelling merit, but lots of self-referential “takes” on ideas already familiar to the audience. It’s very much like reading a behind-the-scenes brain-storming session. Astro City is undoubtedly a masterpiece of the form, but I’m not sure how long superhero comics can reach audiences by having nothing but this to offer.

Reading Comics: and some recent Batman, too

After finishing the last two issues of Doomsday Clock, my superhero comics taste buds had been awakened, so I headed over to read up “some modern Batman, let’s see what they’re doing with it”. A largely arbitrary impulse, except in that I’m probably a bit fonder of Batman than most DC properties; it’s not that I like crime thrillers better than proper superhero stories, but rather that Batman has in my experience been of higher quality since let’s say the Crisis on Infinite Earths (mid-80s, that is) than the other stuff. At its best Batman has presented some seriously good crime thrillers: grim, despaired stories of insanity and immorality. Most other superhero comics lacked a similar thematic niche, particularly in the ’90s and early ’00s, whence my sense that Batman is sort of a step above its mainstream fellows in overall quality.

So anyway, what I ended up reading this week was the on-going run of Rebirth Batman, the most recent reboot of the title started in 2016. This being a flagship title for DC, it obviously has a number of sister series running in parallel, like Detective Comics and Nightwing and whatnot, a massive amount of comics page being published, with stories criss-crossing nilly-willy. I’ve engaged in chronological reading at times to make sense of particularly thick wickets of constantly crossovering parallel publications, but here I limited myself to reading just the one title, #1-#87 or so. I happily discovered that the series was much more readable like this than some found in the history of superhero comics; there were certainly stories that appeared largely from thin air (having been backgrounded in other publications), but overall I never felt it completely impossible to follow the storyline in the way it would have been in some e.g. late ’80s Marvel comics that would routinely bounce the same storyline arbitrarily between different serials.

The serial starts strong, by the way; if you’re an old-time reader and want a taste of what modern Batman is like, the first issue isn’t bad. I personally liked the new superheroes “Gotham” (same as the city) and “Gotham Girl”; self-referential again, sure, but with an actual direction they were going to. The strong start combined with the relative paucity of cross-overing makes this a reasonable choice if you have the same motivation I had: to check out what they’ve been up to at DC recently.

As it happens, however, my initial positive reaction was overcome by dismay as the series progressed. It seems that my random snapshot of 80+ issues overlapped with the full run of writer Tom King, who scribed the series until issue #85. A strong start and a singular vision, right? Well, not so: after reading some of the most hilariously badly plotted Batman stories I’ve ever seen I have to posit that while King provides nice ideas and some reasonable psychological drama, he apparently can’t plot at all.

What you get in the storytelling arts by doing good setpiece designs but bad plot? The answer is, perhaps surprisingly, weak theming: because the initially promising ideas never advance through plot, the theme is never explicated as a concretely appearing element in the story. What King offers instead is a weird, weird succession of limp character scenes connected by plot threads so thin and intellectually offensive that you won’t believe it without reading that one issue in the “City of Bane” storyarc where Bane claims to have planned everything in Batman’s life for the last 80 issues — I guess it’s a paper-thin excuse to build pathos for a storyline that’s completely lost direction, featuring six-issue long dream sequences and other delightful diversions.

Gotham (and Gotham Girl, who has her own complementary thing not immediately relevant here), the new character I mentioned up there, is a good example of the consequences of weak plotting: the character’s premise is that a young man whose life Batman saved a few years earlier (in circumstances reminiscent of Bruce Wayne’s own origin story) has gained superhuman powers similar to Superman’s and decided to dedicate his life to fixing the city of Gotham. So far so good, I’ll explicate on the thematic possibilities I see here: the scenario is surely too good to be true from the Batman’s perspective, hiding some sick ploy; is Gotham an “unbroken Batman”, the kind of hero that the city could have had if somebody had saved Bruce’s parents; do Superman-like methods and ideas work in Gotham — an old theme, but always good for another spin. There’s things you can do with a character like this, although obviously you can’t keep them on-board permanently without destroying the status quo.

So there’s some heat there in the character design, let’s peek at what King does with this: in consequent issues we find that Batman is eager to train the two new superheroes in the hopes of their perhaps taking over for him as protectors of Gotham. We also find out the horrible, heart-wrenching price of their powers: the two youngsters have partaken of a venomous source of power that fuels their superhuman abilities from their own life-force; as they say, “two years to fix Gotham” before their bodies give out. The psychology of choosing to take the trade is significant. This could all work — at this point I’m invested in the story. It would be intellectually interesting in a wargamey sense for Batman to bench the two young heroes after learning of their tragic backstory, only to pull them occasionally up to bat when Gotham actually needs a superman-level heavy hitter to solve its problems; doing it would require curing the two of their obvious martyr complex, but it would mean that they could both live. (Which would of course not go according to plan, but it’s nice to think of a happy ending.)

However, the storyline continues: in their first superhero clash, a couple of esoteric Batman villains face Gotham and Gotham Girl, driving them insane. Gotham decides to destroy Gotham City, the Justice League interferes, Gotham fights the entire Justice League to a stand-still. But of course, he’s burned through his power now and dies. Gotham Girl, his sister, is left distraught and aimless; her motivation had always been to follow in the foot-steps of her brother, so now’s the time to take a good, hard look at what she’s actually doing with her (potentially rather short) life.

OK, so apparently Tom King didn’t actually want to do anything with Gotham, being as how he was killed off almost immediately on introduction. Maybe he’s planning to do all the neat things you can do with the character concept with Gotham Girl instead? They’re almost the same character, after all. We can still have stories about the limitations of superhumanity in the crime thriller genre, hilarious character moments with a Gotham-grown Superman expy, and so on and so forth.

But no, what King actually does with Gotham Girl is fridging her, and hard. (Fridging is superhero comics slang for writing a female character out of the storyline in a ham-fisted way; it’s got an hilarious etymology, if you’re into cultural history.) For the next ~80 issues we only ever see Gotham Girl as an inconsequential background character who’s gone “comic book crazy” (think Joker and such; it’s sort of a common ailment in the city of Gotham), babbling incoherently about her dead brother and acting as a weak second-act complication in various plot lines, being manipulated by a criminal mastermind. (Hint: it’s Bane. Don’t ask me how, it doesn’t make any sense.)

I’ll note that by my reading King is not actually misogynistically motivated in fridging Gotham Girl, it just coincidentally happens to be what he does. My primary proof here is the fact that King follows this creative choice with 80 issues of prematurely yet eagerly exeunting every idea that occurs soon after introduction: both boys and girls and much more get fridged in equal measure in a desperate search for pathos.

I’m explaining all this story stuff in a very cursory manner, so don’t get stuck in the minutiae: the point I’m making is that the way Tom King plots his scripts features the cardinal sin of not going anywhere thematically, on account of how he apparently isn’t interested in developing his themes, preferring psychological drama scenes (that unfortunately get convoluted for lack of plot; pure navel-gazing by the end). There’s a lot of soap opera as characters get introduced and removed from the stage, but there’s no thematic build-up, not to speak of thematic climax, so ultimately the stories don’t carry meaning; it’s all empty bluster, not unlike what we had in the Doomsday Clock. This is constant over those 85 issues; I don’t hate the ideas King presents, but it would be better if instead of trying to build some sort of really, really stupid metaplot about Bane he actually stuck it out and told some stories with what he has.

Gentlemen on the Agora

Some top picks from the cultural salon on-going at my IRC gentlemen’s club. It’s been a relatively quiet week for whatever reason.

- The club has tried its hand with an ordinary social media small talk topic, namely “What’s your most awaited new rpg this year”? The reactions are hilariously dysfunctional as social media small talk, ranging from people discussing their own art house rpg campaign plans (with carefully crafted house systems, of course, and what do you mean that doesn’t count) to venomous bitching about new mainstream games being devoid of creativity. The only game gaining unreserved enthusiasm from this particular crowd was Subsection M3, and it’s not like we know yet if it’s coming out this year or not.

- The Glorantha discourses continue, with the catalyzing contributor having finished their read-through of King of Sartar. We’ve discussed the demographic spread of the Orlanthi religion/culture in Glorantha, which sparked an interesting question of my own: given an Orlanthi culture that becomes stably urbanized, what religion does an urban labourer (lower class non-artisan urban denizen such as a servant or warehouse worker or whatever) engage in? There’s no reason for it to be the universal Orlanth/Ernalda initiation for somebody not engaged in agriculture, after all. Specific local city gods rise in importance, but I suspect that urban working class might be mostly irreligious. Religion in Glorantha is, after all, political, so somebody with no stake in the system might not feel like wasting much time with supporting a cult.

- A follow-up to the above: wouldn’t working class be into sports entertainment, like in the Mediterranean world in the classical era? Evidently Gloranthan cities should feature sports-based hero cults with football fans as lay members and professional sportsmen/gladiators as serious initiates.

- We’ve also been discussing Alfacon, a Finnish rpg meet focused on hardcore hobbyist issues like game design, rpg theory and community building. The event is in a couple of weeks and I recommend it to anybody with serious interest in the hobby. I’ve been in the habit of going myself, but this time around I plumb forgot about it until the December, which was too late to offer programming, so I’m likely going to pass on it this year; I’m lazy enough that I generally don’t bother with conventions if I don’t have some pressing commitment to go.

January polls final stretch

The article poll has been accumulating votes on steady pace; it’s listing 23 votes at this writing, which probably represents an average of a bit under two votes per person (I’ve no real idea, having turned most ID tracking off), so a dozen voters or so — easily enough for you all to form an useful sounding board.

The front-runners are similar to last week, except Cyberpunk 2020 Redux has seized a narrow lead. I already did a little bit of sketching for the article, so that one’s probably happening. Storyboarding is doing strong as well, so I’ll see about doing that as

The poll will be open until the end of January, though, so there’s still time for one more round of votes. I’ll replace the poll with a new one for February, with some new options (and maybe some of the old ones that seem like they should get a second chance). I’ll probably finish the winning article sometime in early February, and maybe a second one in late February if I feel like it. We’ll see how that goes.

[January 2020] What should I write about in more depth?

- The RPG theory of storyboarding (21%, 18 Votes)

- Cyberpunk 2020 Redux (21%, 18 Votes)

- Pointbuy game design (14%, 12 Votes)

- Xianxia old school D&D (13%, 11 Votes)

- Subsection M3 (12%, 10 Votes)

- Review the D&D Immortals Rules (12%, 10 Votes)

- Boondoggle game design (5%, 4 Votes)

- Doing something worthwhile with Star Wars (2%, 2 Votes)

- Something or nothing else (specify in comments) (0%, 0 Votes)

Total Voters: 31

As always, I’m open to suggestions for improving the newsletter. With this issue we’ve been doing this for a whole month, so the general thrust is probably coming clear. Let me know if there’s something I could do to make this more interesting to you.

“plum” or “plumb” forget, not “plump”