Again lagging behind on the newsletters and really everything else, damn me. Nothing to it but to keep trudging on.

Sandbox hex maps as operational theaters

We recently started a new operational theater in Coup, so I guess I’ll take the opportunity and explain what “operational theater” is here. It’s a kinda interesting structural feature of longer-running D&D sandboxes. It’s either something that emerges from the game’s structure on its own, or something in the way I play makes it appear. But first, some basic concepts:

Sandbox campaign: A D&D campaign where the players determine what adventures will be played by maneuvering around a world map. I also like calling this “advanced” D&D to differentiate from “basic”, for all that these terms are already fairly congested. The key distinguishing feature is that advanced campaigns possess playable, dynamic operational and strategic levels of play, while basic campaigns consist of modular scenarios without those higher levels of maneuver.

Levels of warcraft: Warcraft traditionally conceives of dynamic conflict in terms of practical decision-making loci that flow from upper level (long-term, broad scope) to lower level (immediate, narrow scope). The traditional basis for this structural modeling lies in the way human governments and armies have distributed decision-making duties historically, so the “levels of warcraft” are sort of distinct, independent but related disciplines that concern tasks and duties that a given decision-maker in a given position has to master. These are the common “universal” levels as I usually see them listed:

Martial technique — How to throw a punch. D&D traditionally black-boxes most of this level of warcraft; charop rules detail and circumstance modifiers may affect it, but on the most basic level a +2 attack bonus is all you need to know about it.

Military tactics — How to maneuver on the battlefield. In D&D the tactical concern is dungeon warfare maneuver, having to do with managing the unknown, planning retreats, arranging corridor fighting formations, using specialists intelligently, camping, etc. Basic D&D is a skill-based game on this level of warcraft.

Operational art — How to choose battles. The operational level in D&D is foremost about expedition management, and it is generally only fully dynamic in advanced campaigns; it’s not uncommon for GMs to fudge the various issues involved in equipping the expedition, wilderness travel to target dungeon, managing manpower and generally maintaining expedition capability to perform in the dungeon. In advanced campaigns this is all fully in play, however; how many days you have to solve a dungeon ultimately depends on your operational logistics, for example. (Large dungeons may involve operational maneuver within the dungeon itself, too.)

Military strategy — How to win the war. The “war” in D&D consists of the ultimate life goal of the adventurers, namely becoming stinking rich (and dealing with the consequences, the game keeps going afterwards). The most pressing strategic questions in sandbox D&D are generally about choosing adventures to engage in and managing downtime between adventures in a fruitful way. It is fair to say that the higher we go up the strategic scope ladder, the less often actual play addresses these concerns; most of the play-time is always spent in tactical maneuver even in advanced campaigns, after all!

Grand strategy — What is war, even. D&D, due to artificial focus involved in games, begins by assuming the grand strategic goal of filthy lucre and the grand strategic means of dungeon adventuring. It’s sort of fixed scope, players of even advanced sandbox campaigns do not generally need to start by philosophizing about whether their character wants to be an adventurer or a baker. However, long-term the game absolutely involves concepts and choices that are grand strategic in scope. Whether to engage in domain play at Name Level or not, for example.

Operational scale: Operational scale play in D&D usually involves either wilderness maneuvers or urban maneuvers. Setting the latter aside (it’s not a very prominent game mode in comparison), we can say that the stage and type of play that is most involved on the operational level of play is wilderness expedition, often implemented as hexcrawling. In this sense the hex scale is the scale on which operations occur.

Operational theater: The “theater” of operations is the scope box that operational art defines in determining relevant information and concerns for planning an operation. In D&D expeditions the theater consists of the geography over which operations occur. Because these D&D operations are hexcrawling, basically: your operational theater is the hex map over which the crawl progresses.

So that’s all a very long-winded way of saying that “operational theater” is the same thing as the hex map. Read on, because the following is maybe a bit unexpected.

Multiple operational theaters

Because D&D operations revolve around expeditions, and expeditions begin and end at HQ towns (a safe place where the adventurers can stock equipment, hire mercenaries and divest loot), I’ve found that the practical operational theater at any given time is defined by the HQ town: expedition maneuvers occur in the surroundings of the HQ town. This tendency does not arise from the hex map or other formal structural conceits, but rather directly from the underlying wargaming conundrum of how these small-scale exploration and filibustering expeditions work.

So while it’s true that the operational theater usually fits on a single hex map, it’s also true that the theater is neatly defined by the logistical gravitation of the HQ town. The exceptions are of course always interesting, like how you could have multiple small towns connected by good travel connections, granting the party flexibility in launching any given expedition from any of them. Or the operations in a more challenging scenario might be headquartered at a ship instead of a town. Plenty of variation.

But in low-tier D&D, it’s generally a town that defines the operations. A town, and the surrounding countryside maybe a week’s travel away, so like a 150 miles circle around the town, more or less. In my experience more than that is rare at low levels because of the difficulty of surviving long wilderness journeys, and because there’s almost always a suitable HQ available closer to the dungeon than that.

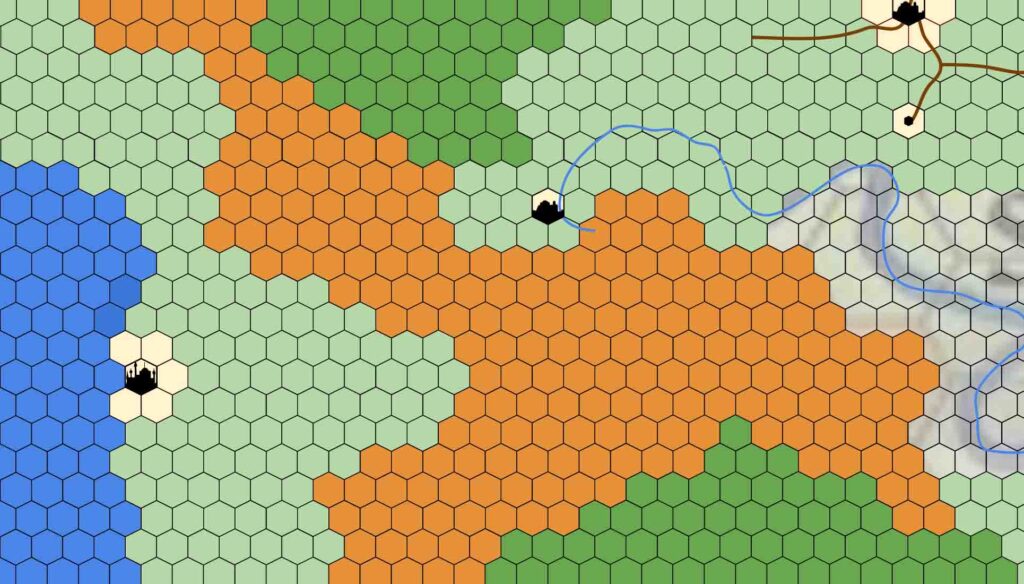

In 6-mile overland hexes that I like to use for hexcrawling the natural logistical definition of the operational theater tends to also equate to a single sheet of hex paper, more or less. We can usually fit the HQ town and surrounding countryside on a single sheet. This doesn’t technically speaking need to matter much, but it does create a certain tool-usability feature in how players perceive and relate to the wider setting. I’ve been supporting the 6-mile maps recently with 30-mile regional maps as well (you can fit an entire preindustrial kingdom on one of those!), but ultimately these 6-mile hexrawl-aquarium sheets are the real terrain over which the game occurs.

And, the most interesting part: everything I say about the usability of the single-sheet operational theater would of course be true as well if the entire campaign happened to fit on such a sheet. That’s often how people describe a full panoply sandbox game: you have this hex map that you can wander around. But that’s not quite it in the long term, it’s more interesting and there’s more emergent structure to it: a given operational theater, a given HQ town and its surrounding wilderness, will last you for something like 20–50 sessions of play. At some point you’re going to get to expand the adventures strategically! So that regional map, or whatever you use to form a sense of a wider world, gets a workout. And the players get to start collecting an entire folder of local maps, one for each operational theater the campaign spreads into.

Moving from one operational theater to another is always a fun task. It implies that the adventurers are going to take a longer overland trip (often by well-traveled roads, of course), and while they’ve probably grown well accustomed to maneuvering in their starting operational area, now we’re going into the unknown. Time to start a new hex map.

For a more linear basic campaign this sort of thing is largely a “wilderness reset”, but for a free sandbox my experience is that having the campaign expand to a new operational area rarely means leaving the old one behind: you probably didn’t finish all the obscure, hidden, over-leveled adventures in the area. New events occur. And of course not the entire character roster just roots up and leaves “home” at once; more likely it’s just a single distinct party that decides to pursue opportunities further away. So you end up with this unitary campaign occurring not so much across an ever-widening area (as this is often described) as across multiple independent but interacting loci of operational action — multiple operational theaters.

One more observation about operational theaters: D&D adventure module design tradition has an interesting feature where module designers love to give you a “wilderness context” to the adventure. Often these wilderness contexts for the dungeon are unfortunately half-formed to be treated as entire operational theaters by themselves, so you need to do a fair bit of adaptation work, often just ignoring the material. But it’s also somewhat common for the designer to give you what amounts to a small starter operational theater on its own. B2, Keep on the Borderlands, for example: the scale is comically small, but technically speaking the adventure module presents an entirely workable starter for an operational theater centered upon the keep itself. It has everything you’d expect of a small operational sandbox like random encounters, secondary locations, and of course the HQ keep.

Summary time on this blather: my point is that paying attention to the operational theater as a naturally emerging structural element in how a campaign grows and develops is smart because it seems to me to be the natural structural base unit of a long-term campaign. You will probably not finish a campaign in the scope of a single operational theater; we manage to at most transition to mid-tier opportunities before adventurers start naturally hankering for new vistas. In a long, fully formed campaign (I am thinking of games that last dozens upon dozens of sessions; remember, you can feasible adventure for up to ~50 sessions in a single operational theater) I believe that consciously managing this structure makes for more ordered and effective GMing.

I’m going somewhere with this, it’s all background for my reviewing the operational theaters currently on-going in the Coup campaign. In the spirit of attempting to limit the length of these newsletters, though, I’ll try a new thing: stop here and continue exploring this matter in the next issue. We’ll see how that works out.

AP Report Pile: Coup in Sunndi #50

Also, here we come to the reason I decided to discuss operational theaters: I had to establish a new one again for our Sunndi campaign. The adventurers there have really been getting around! They’ve ~30 sessions less on the campaign clock than the online group, and we’re now starting the fourth operational area for them against the two that Selintan Valley has been adventuring in. More on that in the next issue, but the point is: I prepared some basics for the Hollow Hills campaign theater after we talked about the matter in the last session, so now I was ready to start adventuring in the area! I still want to go back to Dhalmond to see my plans for the region bear fruit, but I’ve got plenty of patience, we can go adventure with the hill-men in the meantime.

As a reminder on what’s going on, the Magister’s Mine Adventure is a characteristically mid-tier affair revolving around Magister (nee Cultist), the single most successful adventurer in Sunndi so far. Magister’s been making scores as a Chaotic Evil fixer, working as a gofer and second-in-command for various colorful CE NPCs. The other players are surprisingly on-board with Magister’s soft-spoken treatchery; I think it’s hilarious how he hijacked an entire party of Evil PCs and sold them one by one into slavery at the Temple of Doom. Defined the campaign for a long time.

So Magister had been doing fairly well at the Temple of Doom, but his fast rise and entanglements in the temple politics were kinda-sorta-maybe coming home to roost, so instead of choosing sides between the Order of Fear (LE blackguard faction) and Khata the Werepanther (a CE strong female cannibal) in the brewing Temple Civil War arc, he invented a new quest far away for himself: with the support of his on-and-off mentor, the mysterious golem-crafter Toyman, Magister set out to supply the Temple with renewed supplies of black agate (onyx), a keystone ingredient in the local necromantic traditions.

This all was established about half a year ago in real time, back when the rest of the poor Beast Society adventurers were preparing for the Tournament of Fear and whatnot. The game’s just been wandering around other concerns… well, no more! Time for Magister to stride forth. The Hollow Hills are a known major source of agate mining, in addition to metals that various Sunndian governments have been taking out of the Oerth for centuries. (The hills are “hollow” for this reason, metaphorically exhausted.) With the Aerdian imperial government gone and Sunndi only recovering from the war of liberation, the hills are only ruled by the hillmen themselves now.

I could theoretically have worked out all the details for what lies in the Hollow Hills in advance, but what with apparently not being able to meet even actual work quotas, I’m not going to be spending several days of work on that sort of stuff. Instead, we’re running the Hills with RNG methods: I whipped up a basically empty geography map for the area, made a list of the kinds of things that exist there, and went into the session ready to randomize the details. Here are the central ideas I came up with, to further build around:

Half a dozen major mines: The roads and what used to be civilized logistics in general in the area centered around the mining operations. There’s kobolds in them there abandoned mines, obvs, and they’re a major interest in Magister’s Mining Adventure, so…

Hill Tribes: There’s ~10k natives living in the region, old Sunndian population with the “savage” tag. Great slingmen for civilized armies, sheep-herders, clan society. My conceit is that each clan (1k–2k people each) has an Alignment that’s 1/6 Good, 4/6 Neutral and 1/6 Evil; I would continue generating new clans until I have generated one Good and one Evil clan, and then stop. This would form the basis for figuring out the local clan political situation, should that come to matter.

A harsh yet beautiful land: The hills are rocky, with sparse water; just 1/6 chance per hex entered to find fresh water without specifically wasting time looking for it. The hillmen know where the watering holes are, of course. Similarly, each hill hex has a randomization routine for featuring “cliffs” in their vertices (hex sides), major cliffs or ravines that show up on the 6-mile map as terrain obstacles. Potential to complicate overland travel for those who have yet to map where such obstacles lie.

I didn’t form a strong prior opinion on the random encounter table for the area; I did consult Gygax’s original encounter tables in the Greyhawk setting material, but they’re ultimately kinda generic. Nothing I particularly object to, but I’m sure the area will develop a bit more character with time. I’ll get around to finalizing the encounter table at some point.

Adventure-wise, the Hollow Hills are a marginal region with up to ten adventure seeds. Mainly small-time abandoned mine stuff, one imagines, but there are a couple of larger and more ambitious opportunities I have in mind for the region.

The hexcrawl has the pride of place in Magister’s Mining Adventure, anyway; that’s where the party will find their agate mining prospects, on the wilderness map. The first thing to do here is for the adventurers to learn to survive in the Hills, we can worry about adventuring prospects later.

Strategic underpinnings

Speaking of the actual session events, this was the Magister’s show all the way: he’d left the Temple of Doom alone to enact his mad mining mission, so it was up to him to hire some more player characters to help him with the task. As tends to be the case with players, Magister was pretty hands-off about dictating what kinds of characters the other players could bring into the mission; for some reason players don’t want to dictate even when it would be perfectly justified.

I thought that the way the adventure opened strategically was very nice in how the adventurers had two viable entry directions to the Hollow Hills: coming from the eastern parts of Sunndi, Magister could plan to travel through either the principality of Eyedrin or the principality of Dhalmond, both of which happen to be well-documented earlier stomping grounds in the campaign. The choice in the angle of attack would determine a host of minor and major issues about the expedition plan.

Another source of strategic complication was the Magister’s demonic politics positioning. While a low-level Cultist can have a fairly performative relationship to the demonic hierarchy, just doing the occasional service in exchange for magic powers, Magister is getting to a level where the demon lords want to use him as a tool of operations in the Prime Material Plane. A more passive player would probably welcome the role of a tool for how it removes all responsibility for strategic direction, but Magister’s more of a struggling thing who wants to retain some personal autonomy.

Magister originally came into demon worship through a failed Order of Fear initiation that caused the young man to hear the Song of the Demogorgon. Skipping the theological details for now, Magister’s selfishness and unwillingness to sublimate his identity to the call of the wild has caused him to serve Demogorgon’s interests in an unusually intellectualized way. Unknown to the player, the entire Magister’s Mining Adventure conflicts with the Demogorgon/Orcus struggle for influence in the region of Sunndi: necromancy is Orcus’s bailiwick, and empowering the Toyman and other demonic necromancers might threaten Demogorgon’s current supremacy as the demonic patron of the Temple of Doom.

So what this ended up meaning in practice is that Magister has started having prophetic dreams as he travels south-west, towards the Hollow Hills. Demogorgon (who hasn’t contacted Magister in person in the past) specifically commanded him to stray from his quest and instead go evangelize Demogorgon in Darkness Beneath. A worthy adventure that, no doubt, and surely not out of line as a demand for someone supposedly loyal to the demon lord.

However, then Magister got a night emission from Orcus as well the very next night, and here’s this other demon lord that wants the exact opposite: Magister would surely be richly rewarded if he stuck to his guns and indeed garnered that large stash of black agate for Toyman; it would surely be of decisive help in the long-term plan of toppling the Sunndian state apparatus. Magister should well consider the benefits of aligning himself with a greater lord.

This sort of loyalty struggle between a cultist and their distant demon lord is difficult not so much due to the control exerted by the demon lord (minimal as it is), but rather because the Pact of Loyalty that allows the cultist to use Demonic Power as their own only works if the cultist is truly loyal. So whatever Magister does, he’ll need to maintain both the social understanding of loyalty and his internal belief (self-delusion as it may be) that he remains loyal to Demogorgon. Or maybe he needs to switch to Orcus, who knows.

Ultimately Magister chose to keep with the mining quest, justifying it to himself in various ways, but also asking Orcus for aid in fulfilling the task, so I think we all can see what way his loyalties are pulling now. Attracting Magister into his service would evidently be a minor coup for Orcus, so Magister got the red carpet treatment: Orcus inscribed his soul forcibly with the Warlock talent of Inspire Conjurer, enabling Magister to then get further instruction in Geosense, a psionic talent (Magister is psionic, btw) that would prove instrumental in his locating the desired onyx buried in the Hollow Hills. Pretty nice!

We had some adventures in this session too, right?

Well, we sure did do a bit of stuff. The main feature was this vaguely Silent Hill -esque cursed village thing that was established in the setting dozens of sessions ago. The village, which the players have smartly avoided before, happened to be on the route through Eyedrin and into the Hollow Hills, and for whatever reason Magister and his new team of adventurers decided to go visit the locale.

This is, to be clear, one of those adventures that have so scary adventure hooks that only an idiot insists on entering. The village was cursed when adventurers desecrated the tomb of an Apostle of Wastri, and the villagers collectively conjured the Doom upon the grave-robbers, and in the process, themselves. So the place is an obviously cursed hellhole of a ghost town now, with some intricate curse-puzzle of magical rules set determining what happens to anybody who goes there. But that does really matter if you know that it’s gonna involve sparty splitting, nighmare realms, stalker-murderer monsters and death…

The party made it fairly easy for the local rules of reality to “kidnap” one of the PCs into its nightmare realm by voluntary tactical separation. While that one character was adventuring in the subterranean reflection of the abandoned ghost town, the rest were busy looking for the tax moneys hinted at in the town’s backstory. Finding the money but not their ally, the adventurers shrugged in true Chaotic Evil style and abandoned the poor fool. There was around a thousand silver coins in the tax chest, so just a ~50 GP or so, but at least it was easy for everybody except that one guy.

After that we started scrabbling at the hexcrawl a bit, got properly out of the reach of civilization into these unpopulated hills. More on that next time, I’m sure. All in all, we didn’t notice it at the time, but this first session of our Hollow Hills adventure was fairly sweeping! Appropriate for session #50 of the Sunndi campaign fork.

State of the Productive Facilities

I’ve had several weeks of hatefully low productivity here, again. Basically the entire month of March, gone down the drain. I don’t even have any particular reasons to show for it, just life seems to be ill-suited for managing to write. My new favourite explanation is that while humans superficially seem like interchangeable units, in secret some of us have rotten brain meats, and therefore we’re unable to muster the energy and concentration to be productive. I hate myself.

I guess that’s enough self-flagellation for now, though. Onwards. I’ll write several newsletters with quickened pace to get back to schedule on that, then try to get back to Muster.

Fascinating stuff, as usual. I’m especially interested in concrete observations like map sizes here.