On the one hand, I’ve bounced back from my usual morbidity, and am actually being fairly productive this week! On the other hand, yesterday I worked on what must be the most useless thing this year. Let me show you.

Hex tiling a planet

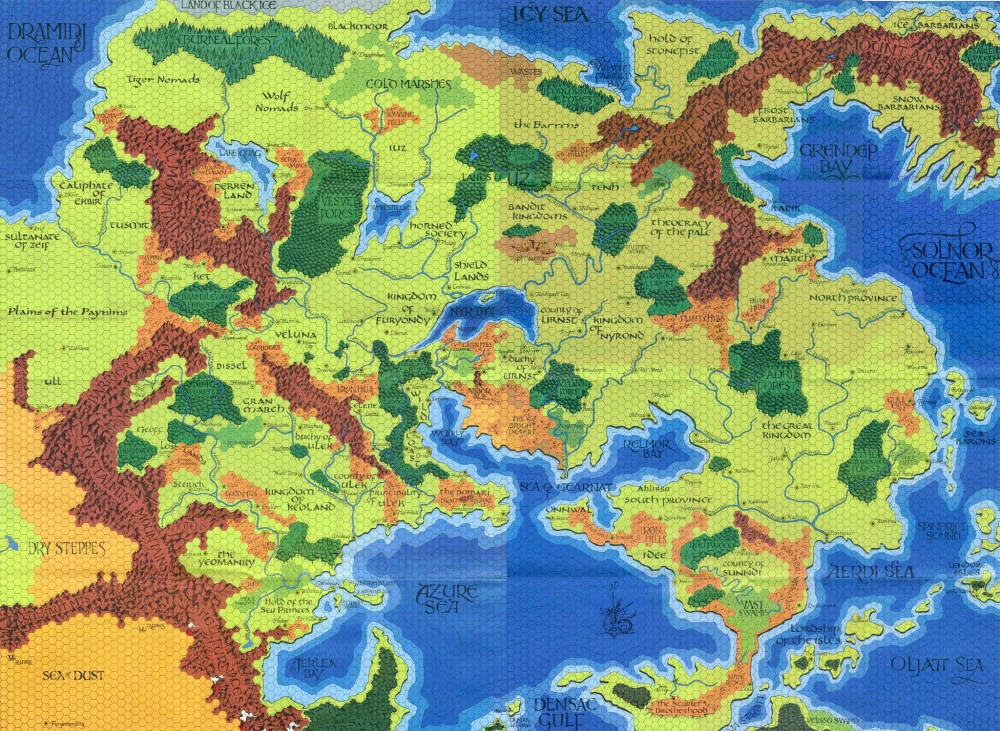

I was working on a new operational theater for the Coup campaign (the Hollow Highlands, the players in the Sunndi game decided to go hunt for abandoned mines in the area) this week when an old bugbear of the impure mind started harassing me about the map projection inaccuracies of the Darlene map, the original Greyhawk campaign map.

The map is a large 145 × 97 hex continental presentation of the fictional continent of Flanaess that came with the original Greyhawk campaign setting. The map is overlaid with a regular hex grid, with the hex scale indicated as 10 leagues (30 miles). This map is arguably like half of the campaign setting as it is; as I’ve discussed before, the Greyhawk setting amounts to little except the map and the short capsule descriptions of several hundred polities and geographical areas of the continent.

So what has bothered me about this for some time is that a large hex map of an entire continent like this is large enough that planetary curvature would start affecting the flat map projection. This causes a fun little paradox that I’m quite certain that didn’t bother Gary Gygax at all when developing the setting, but it does bother me. Partly it bothers me because Gygax chooses to discuss the astrography and geodesics of the setting in such great detail: he gives us enough information to run himself into paradox.

Here are some pertinent facts that the Greyhawk box gives us:

The map is uniformly regular: This is not only directly stated, but it also kinda obviously needs to be the case, right? The map exists to be hexcrawled, and all the procedural routines of the game absolutely rely on the hexes being 30 miles across consistently across the entire map. This tells us that the world is either flat (clearly contradicted by text), or (more reasonably), the map projection is reasonably distance-preserving that it makes sense to overlay a regular hex grid at all.

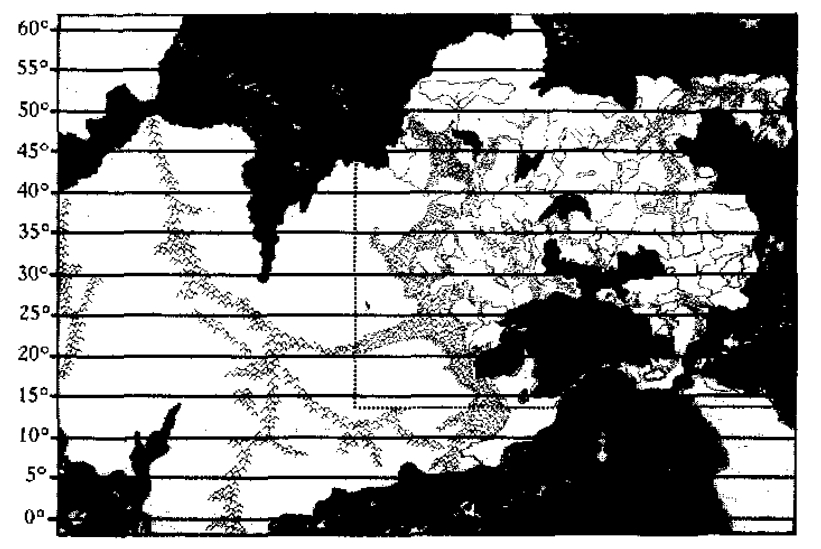

The map is an equirectangular projection: This comes as a bit of a surprise in light of the above, but the weather-modeling section (it’s one of those crazy cook digressions in the book, an entire chapter about the weather patterns of Flanaess) has an extremely explicit map and tables that straight up give us all the scaling and latitude information we need to identify the map projection. As the latitude map clearly indicates, the Darlene Map is supposedly in what is known as the “equirectangular projection“. We can tell because the latitude lines on that map are placed at regular intervals and are entirely straight, on a map representing a land-mass on the surface of an Earth-like planet.

The above two facts are in absolute contradiction, so one has to give. Specifically, an equirectangular map distorts land-masses at high latitudes, making them appear wider than they really are. Or, to put that into hex crawling terms: the hexes higher up on the map should be considered wider (but not taller) than the hexes lower down on the map representing a northern-hemisphere landmass.

It seems from some superficial net-crawling that the equirectangular interpretation of the Greyhawk map enjoys at least some popularity in the scene, presumably among people who do not actually hexcrawl and are therefore comfortable with insanity. For me this interpretation is obviously unacceptable: the hex map is vastly more important than some random throw-away “I don’t understand geography” weather map inside the covers, so I’ll just ignore that and assume that the hexes are essentially correct.

Which then, of course, leaves me with the question of what it actually is that the Darlene map is presenting. It’s not a flat world (option in these fantasy affairs), that’s abundantly clear, and we know that the planet is near Earth-sized, so there are limited options in this regard.

Geodetic icosahedron whatsit

The planet of Oerth, that the continent of Flanaess sits upon, has an important literary property:

Earth-like: A significant literary theme of Oerth is that it is part of the “mirror sequence” of alternate Earths, of which our world is one as well. Apparently Oerth is at the apogee of magic in this sequence, whereas our world is particularly non-magical. This is relevant as a literary conceit here because it explains how Oerth is generally just very Earth-like, and why this is, and how finding unnecessary differences is contrary to the heuristic: Oerth should be like Earth, except where it is not. An useful way to think about this is, I find, to imagine both Earth and Oerth being built from the same box of Lego blocks. Familiar, but not the same.

The setting has historically accumulated quite a bunch of minor geodetic differences from the Earth, like a significantly higher axial tilt (of course without affecting the seasons) and the planet supposedly being slightly larger than Earth and so on; I’m comfortable ignoring these ideas until clear demonstration that they actually do something useful, and otherwise assuming that the planet is earthlike in its physical constants.

But the important part is that Oerth is a planet, and that means that it can be mapped out like a planet. My favourite planet-related hex mapping tech is, of course, the geodetic icosahedral projection familiar from Traveller: it’s ideal for translating planetary curvature into a flat hex map in a reasonably simple, gameable way. Most importantly, distances and areas are preserved reasonably well in an icosahedral projection, which means that just overlaying a hex grid (or constructing the entire map of hexes, as the case may be) isn’t the absurd pretense it’d be in many other projections.

To my surprise, I couldn’t find any efforts at putting the Greyhawk setting on a geodetic map like this, so I had to do it myself. I’ll discuss the conclusions in a bit, but for educational purposes I’ll explain the icosahedral geodetic a bit more first. Just in case it’s not old hat for you already.

The fine art of mapping a d20

The icosahedral geodetic is as far as I know a gamer trick for making planets into hex maps; I’m not aware of it being popular as a map projection otherwise, except in occasional curiousities. The basic idea is to take your planet, map it on an icosahedron (a 20-sided die, a regular polyhedron with 20 triangular faces), and then cut the shape apart into a flat map representation. The map you end up with (refer above to the Earth example) consists of 20 triangles, which in the standard presentation are cut apart at the north and south poles to spread the whole out flat.

When reading this type of map, it’s important to understand how the edges connect; unlike your conventional world map that connects from left to right (and has weird things going on at the top and the bottom), the icosahedral forms these distinctive “flaps” where the map jumps from the edge of one triangle to another. You could fill in the flaps by stretching the map, of course, but not doing that (so as to be able to overlay a regular hex grid) is the entire point of the exercise here, so we’re stuck with the flaps.

Hexes and triangles have the nice property that as long as the triangle’s height is divisible by the hexagon’s height, the triangle can be tesselated (tiled over) by hexes in a regular way. Practically speaking you’re left with half-hexes on the edges of each triangle, hexes that are shared with the neighboring triangle. It’s a matter of taste as to whether you want to draw these border hexes on the map as half-hexes that connect with their other halves in the next triangle (which might not be visually adjacent on the flat map), or if you’d rather draw that same hex in two different places in the map drawing, with the understanding that the two map locations are a single hex that just happens to exist visually in two places on the map.

This method of covering a planet (or rather, an icosahedron) with hexes causes the kinda charming situation where the corner points of the twenty triangles, 12 of them in all, actually end up being pentagons instead of hexagons. The icosahedron is not round, after all, and much of the geometric distortion gets concentrated in these points, to the outcome that they actually only have five regular hex neighbours. Every other hex has a normal neighbourhood, it’s just these twelve that are weird. You could map a planet onto an icosahedron however, but conventionally one of the points is placed on the geographic north pole, one at south pole, and the other ten end up going around the planet in two chains of five, kinda like tropical longitudes. (Exactly like, in the case of Oerth; weirdly Oerth’s axial tilt causes the tropics to fall exactly between these points in this projection.)

As I mentioned before, the icosahedral geodesic has many favourable qualities for hex-crawl gaming purposes. Flat maps of globes will always lose out somewhere, there are no perfect solutions, but for hexcrawling specifically this is great. Consider:

Distorted directions: It is true that this map projection does not retain straight lines; if you draw a long line through a map of this type, the resulting path would not be straight in reality, and vice versa; each time a line crosses from one triangle to another it goes through an implicit 60° turn. (You can observe this easily by asking yourself what direction north is from any given point on the map.) I’ll demonstrate this further down below, but for now let’s just note that this isn’t a big deal for hex-crawling, where directions are local (you choose which hex neighbour to enter, rather than choosing a compass direction).

Regular distances: On the other hand, distances and therefore volumes (of land) are only affected in fairly minor and innocuous ways. The projection is overall most most distorted along the vertices (the triangle edges) and points (triangle corners) of the icosahedron, while being less so towards the center of each individual triangle. (Or the other way around, I guess; depends on how exactly you’re projecting the globe on the icosahedron.) In no case does the distortion grow… I want to say it’s like a bit over 10% at worst, but can’t be assed to calculate it exactly right now. Nothing that I’d care about in practical hex-crawling, anyway, as the distortions are fairly arbitrary and don’t cluster into specific parts of the map too much.

It’s a d20: If Oerth is a magical world, and it’s the world where the 20-sided die became the king of gaming, then maybe the planet actually is an icosahedron in shape? That would mean that the hex map is actually very precise, with no appreciable geometric distortion from the map projection. A sort of flat earth situation, except it’s just locally flat.

Putting Flanaess on the icosahedron

So that’s what I was messing around on Friday, fitting the Darlene map of Greyhawk onto the icosahedron. You can see the actual map graphic there in the center of the diagram. The result may not look much visually, but I’ll explain what I did a bit so maybe it’ll be of some idle interest.

First, I cropped my diagram to only show about 25% of the planetary surface, just enough to get a sense of how Flanaess sits on the surface of Oerth. The blue hexes on the map are the pentagons (shown as hexagons in my drawing style, I’ll explain that below): the middle top one is the north pole, with the other four being four of the five northern tropical corner points. The map’s not showing the southern hemisphere at all, or the back half of the northern hemisphere.

I put the map triangles together in a non-standard way here because it better serves the point; the left and right triangles are turned 60° towards the pole from how they would be represented in the standard layout. I hope that’s clear enough, just imagine the Traveller map sheet with two of the top protruding triangles leaning in towards one in their middle, until their tops (the north pole) conjoin. While they tip, their bottoms detach from the tropics area and leave them in the arrangement I show in the diagram. Topologically speaking I’m not doing anything here, the hexes connect just the way they would in the normal depiction of the icosahedron. Just easier to see where the Darlene map goes on the planetary map if instead of cutting Flanaess I move the triangles.

Next, notice that there’s quite a few hexes in this. The projection we’re using is actually rather scale-flexible, it works with any hex resolution. I chose to use 150 mile hexes, as that accords with my usual hex scale zooming: five of the Darlene hexes go into one of these planetary (or continental?) scale hexes, in other words. Although Oerth does have some if not canonical then at least apocryphal numbers for its size and such, I’m treating the planet as being the same size as Earth: 150 mile hex + a tad over 40k km circumference equals an equator 165 hexes long, which in turn means that the vertex length, the distance between two pentagon points on the map, is 32 hexes. That’s probably the most practically useful zoom scale measure for this type of map, the vertex length in hexes. Always necessarily a round number, but in this case I of course like 32 popping up by accident. An old pal he, factorizing neatly into 2^5.

(Yes, that was weird. I studied mathematics some in my younger days; in some other timeline I could see myself being some kind of topology-graph theory-numerologist.)

Moving on, I scaled and situated the Darlene map (or rather a digital reproduction) on the world icosahedron by matching the hex scales for size, assuming that map north is geographical north, and arbitrarily choosing to put Flanaess in between the pentagon points instead of having a pentagon point show up on the continent. As you can see, the map actually scales fairly neatly so you don’t have to deal with one of those pentagons in the middle of the continent if you don’t want to. You can just have one in the western pusta, and one in the ocean to the east. I personally imagine that the pentagon points are probably highly magical and possibly have some of the highest mountains on the planet, and because they’re outside the map, then why not. (If the planet really is suspiciously icosahedric, you’d expect mountain peaks in the pentagon points, right?)

The north-south positioning of Flanaess can be found directly in the Greyhawk setting material — remember those latitudes so carefully marked? It happens to be the case that when I interpret the Darlene map as a flat section of an icosahedron, the latitude information aligns fairly well. This would presumably prove that I haven’t messed up horribly in scaling the planet and such.

As you can see, I’ve added some informational latitude lines in red over the map, so as to hopefully illustrate Flanaess’s location on the planet. I’m showing the arctic circle at Earth-standard 65° (Gygax claims 60°, which is probably closer to correct for the axial tilt here, but I couldn’t bother to change it for now), a couple of helper latitudes, and then the northern tropic (I’m calling it the “Tropic of Richfest” for obvious astronomical reasons), and finally down below Flanaess the equator.

Two remarks about those latitude lines. They’re connected, and depending on your maths level I imagine this is either obvious or incomprehensible:

The tropical latitude splits: The 30° latitude line (which is the tropical latitude on Oerth, remember that axial tilt) happens to completely coincidentally (as far as I can see) fall on the icosahedric triangle line of the map projection. This means that the tropic runs along those doubled up hexes that I’ve drawn two times, on the edges of both of the separated triangles. So where you see that latitude line splitting into two, that’s not actually the world going completely ballistic; it’s the same line, just presented in two places on the map.

The latitudes are not straight: This here is the big fat payoff (yes, sadly this is it, entirely) of this entire investigation: assuming we accept the icosahedral geodetic map projection, it does indeed cause latitude lines to bend around the poles like that. The angular nature of the d20 causes the lines to not even curve around gently, they just go straight and neat following the hexes, and then suddenly at the vertex they turn one hex side around. If we put all the polar triangles there to surround the north pole, the latitude lines would make full circle. The same visual phenomenon doesn’t occur to the equator (or any latitudes in the tropics) in the standard drawing of this map, as the tropics triangles are all tiled neatly from end to end. It’s my moving a couple of the polar triangles to keep Flanaess unitary that causes the “bending”.

What does this experiment mean in practice? Well, we know that the Darlene map hex grid can be interpreted to be part of a rational planetary hex map projection. It doesn’t need to be corrected even if we were to adventure up in Blackmoor, on the top edge of the map. The hexes are where they are.

We do know that the direction of north works kinda wonky in some marginal places, though: The Dramidian Ocean to the north-west, and the Trillorian peninsula in the north-east, are so deep into the northern triangle that they cross into the next triangle. As you can see from the latitude lines, that causes north to flip one hex edge to the side. While this may seem eldritch, it’s no different from the real world in anything except the abstraction of having things occur suddenly at hex boundaries. North is always towards the north pole, which means that when you approach north pole perpendicularly (traveling in a direction “past” it, as you would by going to the corners of a map calibrated to show north at mid-top), the closer you get the more clearly you’re traveling to a direction that is not north.

So that’s the answer to my original concerns about whether I should worry about planetary curvature at the scale at which the game operates. The answer is surprisingly yes, but only if we go into Trillorian peninsula, where I need to remember that north is actually map north-west. Sort of towards the Icy Sea on the map, though still <counts hexes> 19 × 150 = ~3000 miles further to that direction.

That’s such a minor conclusion from a few hours of investigation that I feel like I should have gotten more, but then again, it’s good news that the map is not somehow irreparably messed up. And I did get… some interesting excuses for magical power-spots just off the edge of the map, some player brain twisting reasoning for why compasses get wonky in the map corners, and… it would be really easy for me to draw a 150 mile hex scale map of Flanaess now that I have the map carefully aligned to a grid like that. Well enough, at least if I didn’t spend another couple of hours writing this explanation, too.

AP Report Pile: Coup de Main #73

Still going through the AP report pile… seems like I am still three sessions behind here. Fortunately Tuomas writes perfectly acceptable reports to Discord (really, he’s much more conscientious about that than I am, always putting one down immediately after the session). Tuomas: in case I haven’t said it clearly enough, thanks for these. I feel like I’m writing too much blog as it is, good to be able to just copy stuff in like this. I have a fairly good memory for this stuff (years of rpg experience, of course you’d have an intensely clear imagined space), but with this session also having been over a month ago, it’s good that we have fresher accounts on it.

Knights Temp woke to new day after having ousted the cult from town of Illmire last time. They had lots planned, to meet the mayor and then head out to the swamp to root out the cult in their nest.

The lord mayor Crellmont turned out to be just as sick as his butler had told them. Poisoned, more precisely, or that was what Thrumhal concluded after seeing him. The condition was apparently common in town, so everyone started to suspect mass poisoning, maybe the town well? In other news, the mayor filled the Knights Temp on the situation, the guard captain was incompetent, the competent sergeant was missing, having gone to investigate nearby old watchtower about bandit activity and that his nephew Zlatko was after his title and suspected cultist.

Knights Temp decided not to act on any of this new information but continue with their original plan to raid the cultist hideout in the swamp. They also had a prisoner from the temple raid and Artemur had used his fey magic to charm the fellow and they had quite a bit of insider info on the place and also a safe route through the swamp.

The GM totally treated the mayor’s infodump here as, well, an intriguing infodump on the local sandbox conditions. There’s outlaws and intrigues, but we had our eyes on the prize; the task is to defeat the dangerous cult, not to run after some random side quests. I’m sure from the GM side the situation seems much less locked down. For us the main relevance of the outlaws out there was in making sure that a) they can’t join forces with the cult and b) they can’t assault Illmire and raze it to the ground while we’re away. The entire scenario had such a feel for us, really; the town’s fate hangs in balance, and the community is rotten in a dangerous way. Prompt, decisive action is needed.

Little did we know when leaving for the cult compound what an absolutely delightful wargame that would become. And I mean this with all the fully ironic knowledge of how some people hate how D&D grinds to a halt when you start to actually plan things out.

Knights pressed on through the rain and local wildlife and arrived at the cultist hideout when darkness fell. Rob and Thrumhal went to scout and noticed some guards with huge dogs guarding the entrance on hillside. Lots of elaborate planning followed in the rain but like these things usually go, everything was undone when it came time to execute the said plan.

Thrumhal and Sven sneaked around and approached the entrance from the top, planning to jump down and surprise the guards and block to the way in. But mystical fear struck at Sven when they got close to the guard post. Sven wouldn’t move closer, so they returned back to rest of the Knights.

New bold direct assault plan was created and executed. Knights shot arrows and psionic fire at the guard post, clearing almost all the guards and causing the huge dogs to charge. The fighting elements easily slaughtered the dogs before they could pose any threat but one of the guards had managed to survive the fire blast and sneaked back in while dodging arrows.

Tense calm settled. Sven true to his ways started butchering the giant dogs, intending to eat one’s heart. Scholarly types started carefully approaching the entrance to gather info on the fear that had struck Sven. Few of the Knights succumbed to the same fear and refused to go closer but dynamic bard and wizard duo managed to steel their nerves and see what actually was inside.

Turns out the guard post was constructed around an entrance to ancient temple entrance of Rackoo people. They also figured out that the fear was emanating from some unnatural entity from beyond reality and the Rackoo people historically didn’t have anything to do with those.

The Knights retreated to cold and wet camp to make further plans.

So there we were, finally stumped! The adventure so far had been thoroughly to our advantage, everything the Knights Temp tried had gone through flawlessly. The sheer astonishment when our carefully plotted assault got flounced by an alien, ruthless psionic aura energized me like nothing else. The early parts of the adventure might have been low-level fun and games, but this now… the Fearmother is apparently (our subtle probing indicated) Aberrant (Lovecraftian Elder God thing), and of a notably high HD count.

We wiped the guards outside the place to get a better sense for the situation, which part wasn’t a problem, but even then, their dogs were Hellhounds… this place feels seriously high level compared to the cult’s stuff townside. Breaking the session after these revelations was welcome as an opportunity to do some deep thinking on what our strategic position even was here. Maybe we shouldn’t even be trying to break into this place?

Session #77 is scheduled for tomorrow, Monday 7.3., starting around 16:00 UTC. Feel free to stop by if you’re interested in trying the game out or simply seeing what it’s like.

Tuesday: Coup in Sunndi #49

My special feature on the Sunndi game last week got me up to date on our tabletop campaign reports, at least, so this one’s from last Tuesday. As discussed last week, we’d had a bit of a party death in the Caverns of Quasqueton two weeks back, so last week we switched focus to the wider affairs of of the principality of Dhalmond. Hunted some outlaws and whatnot. I’m fairly happy with Dhalmond now, it’s shaped into a fairly complete and flavourful little sandbox environment with its own unique charms for low and mid tier adventures.

So when this week’s session rolled around, of course the players declared that they wanted to get out of Dhalmond and shift focus to a different party of characters entirely: Magister of the Song (he’s a demonic cultist, servant of Demogorgon), the single most successful character in the Sunndian campaign fork, has been ignored for the last half year, but now’s apparently a good time to look into his new endeavour. Magister is planning to travel to the Hollow Highlands, ingratiate himself to the local clans, re-open an abandoned mine, and then do some quick strip-mining to get himself a fat load of black agate, a stock ingredient of local necromancy. A great mid-tier adventure to be sure, but… <sad 🎺> did it have to happen at the exact time when I finally completed the GM prep for Dhalmond…

We played the session with the two-man dynamic adventuring party of Sipi and Teemu, the true regulars of the campaign; other players have had various kinds of seasonal irregularities recently, so we’ve had a few sessions with just the three of us. I have to say that I don’t really mind, I think we have a fun and productive team here. The small party suits complicated adventures particularly well.

So as I mentioned above, after last session’s undramatic failure in bounty hunting, the idea of shifting focus to Magister and his adventures was pitched. A small group like this is fairly agile, so while I hadn’t prepped anything on it (I did know about Magister’s plans, the campaign has just had so much other stuff to play that I hadn’t prepared for this particular adventure yet), we could just start talking about the particulars on the spot. Did some fairly informative geographical work, to be specific, figuring out how the Hollow Highlands fit on our maps and what the local social and economic conditions are like. I think we got the players up to pace on this enough to jump into the actual adventure next time, assuming I get around to actually prepping it before next Tuesday.

The Highlands prep and other general campaign maintenance stuff ate up about half of the session, which still left us with time to spare (the Tuesday sessions are pretty long, like 5–6 hours), so we actually did a new cycle of the Dhalmond Outlaws stuff I discussed last week! This time was much more productive, too, and it all fit into a three hour sequence or so.

Next month in Dhalmond (since last session’s events) I rolled a ‘8’ for the number of active outlaws. Because the two from last month were still going, that meant introducing six new bounties. The new outlaws include some horrifyingly high-leveled ones, such as a 5th level rogue mystic, a 4th level half-orc bandit and such. But, there was also… Sam-Em-Ap, some sort of white collar crime figure who first rose to prominence as an accountant of the Caravansary during Dhalmond’s years of political confusion, and then apparently became a drug kingpin when the Caravansary was burned down.

The PCs wanted to go for Sam here because the bounty was fairly good for a low-level target, 1500 GP for the man and a further 1500 GP for his account books! There was an obvious irregularity right off at the sheriff’s office (the divan of the Dhaltown Sardar, in the local jargon) when the sheriff himself came to explain to the adventurers that he would, by the way, be taking half of the bounty money on this case for himself. The PCs didn’t feel like complaining at the plain grift, particularly what with the amusing sub-plot of one of the PCs, Robber-Roope, potentially being recognized by the cops as an outlaw himself. (No idea why, but both players were playing Thieves with local criminal backgrounds here; smart move for a bounty hunting adventure!)

The actual investigation into Sam-Em-Ap worked beautifully, just the way I imagine this bounty hunting stuff to function; I had my information about his resources and movements, and the players had their information sources and other ideas. The characters being Thieves with local knowledge came handy, as we found that one of them actually knew a couple of people involved with Sam’s drugs operation. Starting from that the case started solving itself; some other party might have had to give up when we found that Sam was hiding with the Ticotaco Bandits in the countryside, but these guys ran down his main wine-muller (drug chemist) and found them amenable to selling out his boss for a share of the bounty. The PCs actually went fairly high in their offer, offering the NPC even share in the bounty, so that worked out well.

There was a week of delay in arranging the meet-and-capture of the crime boss, which amusingly proved fairly difficult for the adventurers to wait. One of them clearly went stir-crazy, deciding to start hunting stray dogs for a local butcher (remember, Dhaltown is in the grips of a famine while this is all going on) for something like a copper penny per pound of dog meat. Sometimes it’s just really, really difficult for player characters to let a day go by without doing something “useful”.

The day of the actual pickup involved some bracing urban action, with a surprise assault on the street, tracking the perp to an associate’s place, and the adventurers were lucky, because Sam-Em-Ap had indeed gone to ground in the obvious place, and was still there. He was the elderly crime boss type, but tried to fight his way out. The two 1st level PCs had fucked up the earlier fight on the street, but at least here the boss was alone, and they had better dice luck, so Sam-Em-Ap went down. We finally had our first bounty!

The backstory got pieced together during the investigation, and the PCs finally realized at some point that the unofficial-ish second reward for Sam’s account books was actually asserted by the Sardar (sheriff) himself, presumably because Sam had some dirt on him. Also, some fridge logic that I finally gave the players because it was too funny to keep from them: the original bounty for Sam was clearly 1.5k GP (it’s in the public wanted posters and all), with the Sardar actually offering the second 1.5 GP himself on the side. Except, where would the Sardar get that kind of money? Why, he’d “grift” both bounties, so he’d only need to pay the 750 GP for Sam, and 750 GP for the account books. Neatly tied crime story here, if I may say so!

One of the PCs almost got into trouble for misreading the social situation at the divan (sheriff’s office), suggesting out loud in the presence of the constabulary that the Sardar would be taking half of the bounty. The Sardar wasn’t too pleased and was quick to silence the fellow, threatening him obscurely with the fact that he knew that Robber-Roope was a wanted criminal himself. So that’s where we stand now: the bounty hunters are in bed with a somehow corrupt sheriff, who knows about Roope’s past. Intrigue!

So how about that account book? The adventurers managed to get Sam-Em-Up to talk before returning him to the authorities. Sam claimed that “nobody could ever find the accounts because I didn’t take them out of the office in the first place — they’re still at the Caravansary!” So that’s a minor further adventure hook for the PCs; the Caravansary was burned down a couple of years ago due to the Troubles (as I’ve come to call the Dhalmond civil unrest), so who knows if the account books are still there, but there’s 750 GP in it if somebody were to find them.

A neat detail about the bounty hunting: the bounties are released (given to the claimants) after a two week waiting period to ensure they’re not contested. This flows well into the general scheduling processes of a sandbox campaign, causes a nice forced downtime for adventurers who want to get their rewards instead of chasing some other advenures in the meantime. In this case we had one of the PCs decide to go on downtime to level up from the bounty, while the other is totally going to look for that account book later in the hopes of a second payday. Nice party split caused by different XP totals, basically, as the more advanced Thief doesn’t want to go on a new adventure before getting their 2nd level.

State of the Productive Facilities

I’ve been quite energetic this week! Must be either the increasing sunshine, or that I’ve been eating some D-vitamin supplements recently, or just who knows what. Working every day, I wish life was like this all the time.

On the other hand, the things I’ve been working on have been total manic period bullshit: I’ve basically written 12 thousand words of these damn newsletters between this and the last issue. So there, useful office hours. Not only do I manage to pick feature topics that inspire writing more than I strictly speaking would need to, but the reporting on our D&D campaign gets fairly long as well.

I’m happy with the basic idea of writing a weekly newsletter, but the letter could be just thousand words a pop rather than five thousand, insofar as the external nature of the commitment (“Correspondence is about Diligence”, as the motif goes) goes. I occasionally try to pay attention to going short like that, but far too often the newsletter clocks in at 5k words instead of 2k. Partly it’s because of the stream of consciousness of course; editing it down afterwards would take even more time, so you get these verbal barrages.

Just cut up the newsletters into “Investment Tips, Part I” and “Investement Tips, Part II”.

That would actually make a hell of a lot of sense.

Pingback: Theory review #51 – ropeblogi